When the .ngo and .ong top-level domains were launched in 2015, they represented something groundbreaking in the digital nonprofit world. Unlike the wide-open .org domain that anyone could register, these new domains required validation of an organization's non-governmental status. The idea was simple but powerful: make a safe online space where donors could be sure they were giving to real causes and not fake charities that were pretending to be real ones.

Nearly a decade later, my recent analysis of domain registration data suggests this trust may be eroding in ways that would surprise even the most cynical observers. After examining zone files from ICANN's Centralized Zone Data Service (CZDS) for both .ngo and .ong domains, I discovered that over 5% of all registered domains in these supposedly protected spaces appear to be associated with online gambling operations.

The numbers: out of 9,193 total .ngo/.ong domains currently registered, my analysis identified 471 domains that likely involve online gambling activities. That's roughly one in every 19 domains – a proportion that raises serious questions about the effectiveness of current validation processes.

It's important to note that this analysis represents a preliminary examination rather than a comprehensive, peer-reviewed study. The findings presented here are based on keyword identification and basic website verification to rule out false positives, which while suggestive, may not capture the full complexity of domain usage patterns. This preliminary look is intended to highlight potential concerns and prompt further investigation rather than serve as definitive proof of systematic abuse. More rigorous analysis would require deeper verification methods, manual review of borderline cases, and consultation with domain registry operators.

The Analysis

I analyzed the complete zone files for both .ngo and .ong domains, looking for telltale signs of gambling operations.

The simple lookup started with keyword matching to find domains that looked suspicious. Then, Python scripts were used to check live websites to get rid of false positives. The keywords were numbers and words that are often used in the names of online gambling sites, such as "88," "68," "33," "bet," "win," "vip," "casino," and "poker."

While this methodology isn't definitive (some legitimate organizations might use these terms in non-gambling contexts), the subsequent verification of live websites strongly suggests the majority of flagged domains are indeed operating gambling services.

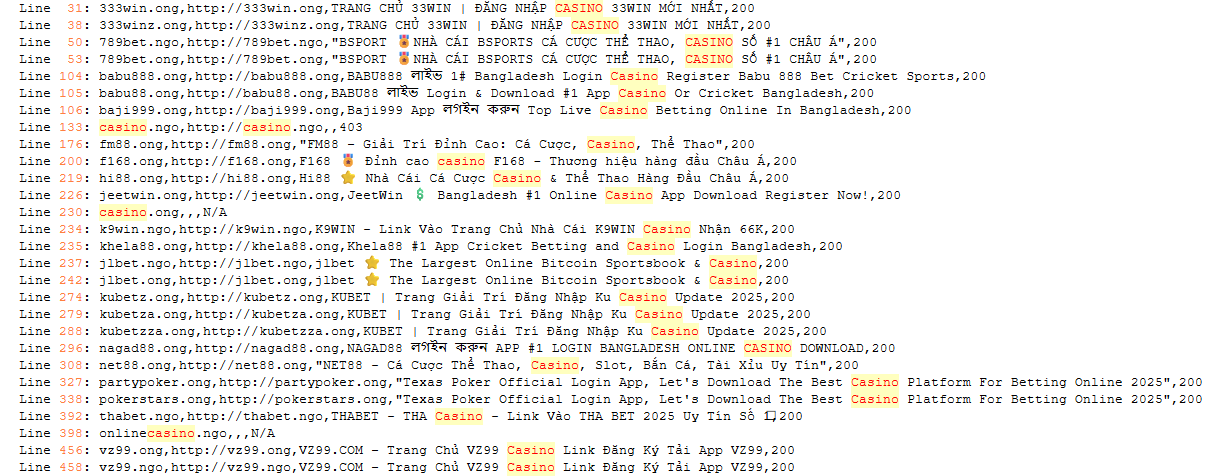

Examples of suspect domains include:

- 188bet[.]ngo and 188bet[.]ong

- bet365[.]ngo, bet365[.]ong, 888poker[.]ong

- fun88[.]ngo, win88[.]ong, lucky88[.]ngo

- gamebaidoithuong[.]ngo - Vietnamese gambling terminology

- 1xbet[.]ngo, m88[.]ong, w88[.]ngo - popular international betting brands

- vip79[.]ngo, 333win[.]ong, 98win[.]ngo - VIP and winning-themed sites

The full list of suspect domains reveals a concerning pattern of what appears to be systematic abuse of domains meant to serve the public good.

How We Got Here: The Erosion of Validation

Understanding how gambling operations infiltrated spaces reserved for nonprofits requires looking at the evolution of .ngo/.ong registration policies. When these domains first launched, they featured rigorous pre-validation requirements. Organizations had to provide extensive documentation proving their NGO status, and domains were immediately placed on server hold while the Public Interest Registry (PIR) directly verified legitimacy. The process required meeting seven specific criteria, including acting in the public interest, being non-profit-focused, and having limited government influence.

The original system also included OnGood, a comprehensive community platform that served as a global directory of validated NGOs. This platform allowed organizations to showcase their missions, connect with supporters, and even collect donations – all within a verified ecosystem that provided additional legitimacy.

However, the landscape changed dramatically around 2020 when PIR implemented significant policy changes to "simplify" the registration process. The new system replaced pre-validation with self-certification, allowing domains to go live immediately upon registration. Instead of submitting documentation, registrants now only need to check a box stating they understand and agree to the policies and certify their organization meets eligibility requirements.

This shift from proactive verification to reactive auditing created the vulnerability that gambling operations appear to have exploited. While PIR retains the right to conduct audits and cancel domains for policy violations, the current system essentially operates on an honor system – asking bad actors to police themselves.

What This Means for the Future

Gambling sites getting into .ngo and .ong domains is more than just a technical policy failure; it's a breach of trust that these domains were meant to build. People who donate to organizations with .ngo domains should reasonably expect them to be real nonprofit organizations. Not only do gambling operations in this space trick users, but they could also hurt trust in the whole nonprofit digital ecosystem.

The timing of these changes also raises questions about priorities. The elimination of the OnGood platform and the relaxation of validation requirements in 2020 coincided with PIR's efforts to streamline operations and reduce costs. While operational efficiency is important, the cost of reduced trust and potential fraud may far exceed any savings from simplified processes.

What This Means for Donors and NGOs

For donors and supporters, this analysis suggests treating .ngo/.ong domains as a positive indicator rather than a definitive guarantee of legitimacy, particularly for domains registered after 2020. The validation that once made these domains trustworthy has been significantly weakened, requiring the same due diligence you'd apply to any other domain.

For legitimate NGOs using these domains, the situation creates an unfortunate association problem. Organizations that chose .ngo/.ong domains specifically for their credibility benefits now find themselves sharing digital space with gambling operations. This may prompt some organizations to reconsider their domain strategy or advocate for stronger validation requirements.

The bigger lesson here is that it's hard to keep trust in digital spaces, not just with domain names. The .ngo/.ong experiment shows how quickly trust can fade when verification systems are weakened, even with good intentions. As we increasingly rely on digital indicators of legitimacy, the systems that create and maintain these indicators become critical infrastructure for trust in the digital age.

Moving forward, the question isn't just whether PIR will address this specific abuse, but whether the nonprofit sector will demand the validation standards necessary to preserve the trust these domains were meant to create. The alternative – a digital landscape where legitimate charities and gambling operations are indistinguishable by their domain names – serves no one except those seeking to exploit the goodwill of donors.

Complete list of suspect domains identified in this analysis - 471 domains

Note: This analysis represents a snapshot in time based on publicly available zone file data. Domain usage can change, and some domains may have legitimate explanations for keyword matches. The findings should be considered indicative rather than definitive proof of gambling operations.